Reineck v. Lemen and Virginia Powers of Attorney

In Reineck v. Lemen, 792 S.E.2d 269 (Va. 2016), the Virginia Supreme Court interpreted a power of attorney to allow the agent thereunder to change the principal’s estate plan. The opinion is interesting for what it reveals about the granting of hot powers (powers that, by statute, must be specifically granted) and certain duties of agents.

Facts

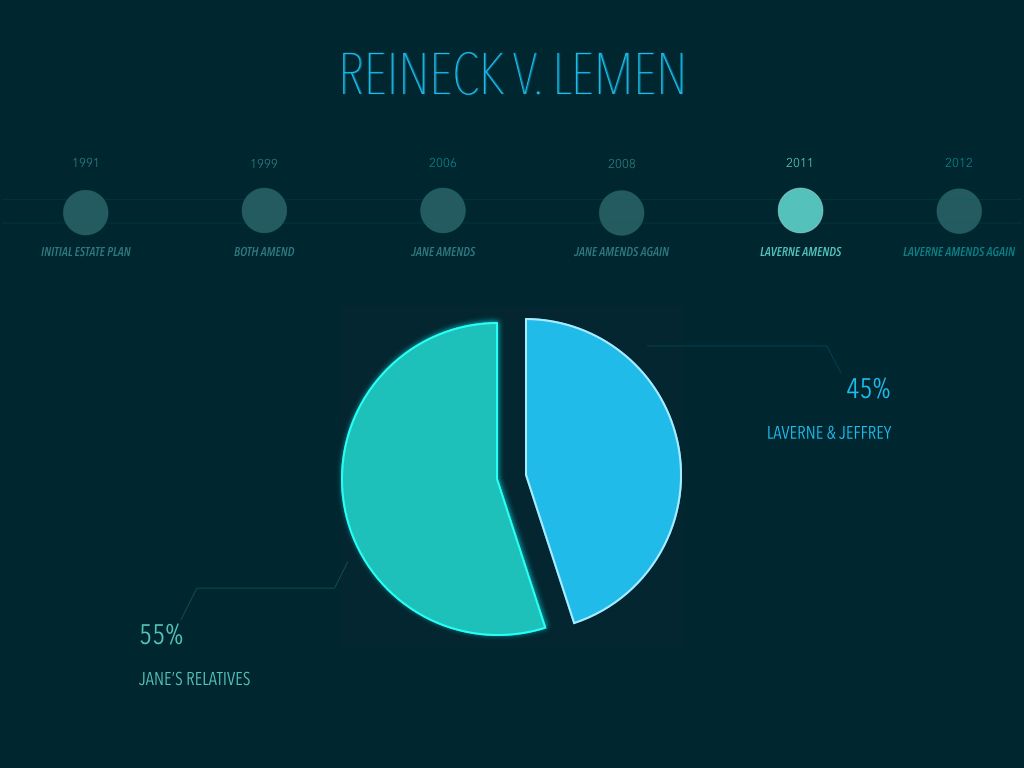

This case is about the estate plans of Frank and Jane, a married couple. Frank had two children, LaVerne and Jeffrey, whom he wished to benefit in his estate plan. Jane did not have children, but she had other relatives whom she wished to benefit.

In 1991, Frank and Jane created revocable trusts with matching dispositive provisions. Each trust provided that 40% of the assets would ultimately go to LaVerne and Jeffrey, and 60% would go to Jane’s relatives.

In 1999, Frank and Jane both amended their trusts so that LaVerne and Jeffrey would receive 45%, and Jane’s relatives would receive 55%. Frank’s trust named Jane as his successor trustee. LaVerne and Jeffrey were named serve as trustees after Jane. Frank also signed a general durable power of attorney, which named Jane as his agent and LaVerne as his successor agent.

In 2000, Frank began to show signs of dementia. His condition deteriorated over the next several years.

In 2006, Jane amended her trust to provide $20,000 each to LaVerne and Jeffrey, with the rest to be distributed to her relatives.

In 2008, Jane amended her trust again. This time, she deleted the provision for LaVerne and Jeffrey.

Jane died in 2011, with her 2008 amendment in effect.

LaVerne and Jeffrey did not find out about Jane’s 2006 and 2008 trust amendments until after Jane’s death. After learning of the amendments, LaVerne, acting as agent under Frank’s power of attorney, amended Frank’s trust. The amendment directed distributions from Frank’s trust to the extent necessary for LaVerne and Jeffrey to end up with 45% of the total of Frank’s and Jane’s trust, with the rest to be distributed to Jane’s relatives.

At some point after Jane’s death, LaVerne, again acting under Frank’s power of attorney, designated herself and Jeffrey as the beneficiaries of an IRA.[1] The IRA was actually an account Frank inherited from Jane.

In 2012, the day before Frank’s death, LaVerne created two new trusts using her authority under the power of attorney. The new trusts provided for LaVerne and Jeffrey only. LaVerne transferred Frank’s approximately $1.24 million of assets to the new trusts. Frank’s assets were distributed according to the new trusts upon Frank’s death.

Apparently dissatisfied with just the assets of Jane’s trust (whatever those were), Jane’s relatives sued LaVerne and Jeffrey, alleging breach of fiduciary duty. The trial court determined the relatives did not have standing to bring their suit. So, one the relatives, William Reineck, became the curator of Frank’s estate and brought the suit again.

The trial court found LaVerne acted within the scope of her authority and did not breach her fiduciary duties. The trial court also awarded LaVerne attorney’s fees against William, personally.

On appeal, the Virginia Supreme Court unanimously determined LaVerne’s actions were proper under the power of attorney but the attorney’s fees should not have been awarded. The portions of the opinion addressing the propriety of the agent’s actions tell us a few things about the powers and the duties of agents under Virginia’s relatively new Uniform Power of Attorney Act.

A. Background on Powers in Powers of Attorney

Virginia’s Uniform Power of Attorney Act distinguishes powers that can be generally granted from powers that must be expressly granted.

A clause authorizing an agent to “do all acts that a principal could do” (a “do all acts” clause), is a general grant of authority. The “do all acts” clause in Frank’s power of attorney granted his agent the power “to do and perform in a fiduciary capacity as my Attorney-in-Fact may deem advisable anything of any character which I might do or perform for myself if personally present and acting.” Such a clause has a specific meaning: it grants a particular set of powers listed in the Code. Va. Code §64.2-1622(C). “Do all acts” clauses are common today. Attorneys either typically include them or typically don’t.

A “do all acts” clause does not grant certain powers, i.e., those that must be expressly granted. The powers that must be expressly granted are often referred to as the “hot powers.” Among them are the following:

- Power to “create, amend, revoke, or terminate” a trust,

- Power to make gifts, and

- Power to “create or change” a beneficiary designation.

Va. Code §64.2-1622(A).

The hot powers are the ones with the greatest potential for abuse. Therefore, something extra—the “express grant”—is required to confer them. I have long wondered what counts as an “express grant” in this context. From this opinion, we learn an “express grant” does not require any particular words. In fact, hot powers can be granted with fairly general language.

B. Power to Change Beneficiary Designation

In determining LaVerne had the power to change a beneficiary designation, the court started with the POA document. The document gave LaVerne the power to “manage qualified retirement plans and individual retirement accounts, including but not limited to. . . the exercise of all rights, privileges, elections, and options that I have with regard to any individual retirement account.” The court then pointed out that “[o]bviously, Frank had the right to designate beneficiaries.” To boot, the court reasoned, its reading of the “exercise of all rights. . .” clause to include the power to designate beneficiaries was “consistent with” the “broad” “do all acts” clause. The court concluded, “[a]lthough the power of attorney here does not track the language of Code §64.2-1622(A) and does not specifically state whether the attorney-in-fact can change a beneficiary, we are nevertheless persuaded that the language in the power of attorney here did grant [LaVerne] the power to make such a change.”

Before reading this case, I would not have counted on a clause like the one in Frank’s POA being sufficient to “expressly grant” the power to change a beneficiary designation. The power to “exercise of all rights, privileges, elections, and options. . . with regard to any individual retirement account” sounds like a grant of general authority, “with regard to any IRAs.” I do not see how the power to “do all acts with regard to IRAs” could be an express grant of a power to change a beneficiary designation. Assuming the power to “do all acts with regard to IRAs” is not an express grant of the power to change an IRA beneficiary designation, I am not sure how to distinguish between an effective grant of the power to change an IRA beneficiary and a general grant of authority.

As an aside, using “retirement plan” instead of “individual retirement account” in the power of attorney could have altered the outcome of this case. The code tells us that “language in a power of attorney granting general authority with respect to retirement plans” authorizes the agent to do only the acts enumerated in Virginia Code Sec. 64.2-1636(B). Changing a beneficiary designation is not among those acts. Had Frank’s POA said “with regard to retirement plans” instead of “with regard to any IRAs,” it may have incorporated only the authority in Virginia Code Sec. 64.2-1636(B). See Va. Code §64.2-1623.

I also would not have counted on the “do all acts” clause bearing on the interpretation of a specific grant of authority, particularly to support the grant of a hot power. I see why the power to “do all acts the principal can do” might be seen as evidencing intent to grant broad authority; however, a “do all acts” clause has a particular meaning under the code (it grants enumerated powers).

The court’s opinion in Jones v. Brandt, 274 Va. 131—the only case cited in analysis of Frank’s power of attorney—seems to provide the foundation for the analysis in Reineck.

In Jones, the agent designated a POD beneficiary for a certificate of deposit. The court explained the rationale behind the longstanding rule that powers of attorney are strictly construed: “the power to dispose of the principal’s property is so susceptible of abuse that the power should not be implied.” The court determined that designating a POD beneficiary on a CD was not within the scope of the policy underlying that rule. Therefore, the court did not strictly construe the powers at issue. The Jones court also cited the “do all acts” clause in support of a broad reading of the relevant grant of authority.

Although Jones and Reineck may be within exceptions to Virginia’s rule that powers of attorney are strictly construed, Jones suggests some hot powers, e.g., the power to make gifts, will still be strictly construed.

Jones was decided in 2007, before Virginia’s Uniform Power of Attorney Act became law. Notably, the new act does not seem to alter the outcome in Reineck.

C. Power to Change Trust

LaVerne used her powers as Frank’s agent to create the 2012 trusts, withdraw assets from his 1999 trust, and fund the 2012 trusts.[2] The court determined the power of attorney granted LaVerne the power to take these actions. In its analysis, the court relied on the following provisions of the document:

- “to do and perform in a fiduciary capacity as my Attorney-in-Fact may deem advisable anything of any character which I might do or perform for myself. . . .” (This is the “do all acts” clause.)

- to “assign, transfer and convey all or any part of my real or personal property, or my interest in such property, to, and withdraw such property from, (i) any revocable trust established by me during my lifetime, or (ii) any revocable trust established by my Attorney-in-Fact during my lifetime which directs the trustee or trustees to administer the trust for my benefit.”

- to “make, execute, endorse, acknowledge, and deliver any and all instruments . . . including, but not limited to, . . . inter vivos trusts . . . for my benefit during my lifetime and/or the benefit of my wife and my descendants after my death.”[3]

The court concluded LaVerne acted within the scope of these powers as to the trust, despite William’s arguments to the contrary. The “do all acts” clause factors into this analysis as it did in the analysis of the power to change the beneficiary designation.

D. Duties of Agent

Virginia’s version of the Uniform Power of Attorney Act imposes a number of duties on agents, among which is a duty to “[a]ttempt to preserve the principal’s estate plan, to the extent actually known by the agent, if preserving the plan is consistent with the principal’s best interest based on all relevant factors. . . .” Va. Code §64.2-1612(B)(6). That duty is waivable by the principal in the power of attorney. The relevant code section that the court cited—Va. Code §64.2-1612(A)(1)—requires an agent to “[a]ct in accordance with the principal’s reasonable expectations to the extent actually known by the agent and, otherwise, in the principal’s best interest.” This is an unwaivable duty of an agent under a power of attorney.

The court determined LaVerne “acted in Frank’s best interests” and consistently with “the provisions of the Uniform Power of Attorney Act, including [Va.] Code §64.2-1612(A)(1).” That section requires an agent to “[a]ct in accordance with the principal’s reasonable expectations to the extent actually known by the agent and, otherwise, in the principal’s best interest.” In support of its conclusion that LaVerne did not breach her duty to act in Frank’s best interests, the court relied on Frank’s apparent concerns with his needs, his wife’s needs, and providing for his children, which are the concerned he mentions in the document. Neither Jane’s relatives nor the preservation of the provisions of his estate plan was mentioned in Frank’s power of attorney document. According to the court, LaVerne’s changes did not adversely affect Frank’s or Jane’s interests, and the children were provided for in the new trusts; therefore, LaVerne’s creation of the new trusts was consistent with Frank’s best interests.

In its analysis, the court somewhat indirectly addressed the agent’s duty to preserve the principal’s estate plan. The court noted that Frank’s original estate plan was made with “parallel provisions” to Jane’s and contemplated LaVerne and Jeffrey inheriting part of Jane’s trust. The implication is that Frank’s “estate plan” was more than just the provisions of his trust: his intent for his descendants to receive approximately half of his and Jane’s combined assets was part of his plan.

The court also pointed out that Frank’s power of attorney relieved LaVerne from liability “except for willful misconduct or gross negligence.” However, the court did not rely on this exoneration provision in reaching its conclusion.

Conclusion

This case tells us a few things about how to interpret certain provisions of Virginia’s Uniform Power of Attorney Act.

Most interesting, in my opinion, are the portions of the opinion on what is required to grant a hot power. The case confirms it is quite easy—perhaps too easy—to grant the power to change a beneficiary designation and possibly other hot powers. The line between an express grant and a general grant of authority is not entirely clear. As drafters of powers of attorney, we might wonder whether we are inadvertently conferring hot powers. To prevent an unintentional grant of a hot power, we might follow the practice of some Florida attorneys and include a provision like the following in powers of attorney: “My agent may not do any of the following unless I have initialed the specific authority below: [insert list of hot powers here, with lines for initials]. To the extent I have initialed the foregoing powers…” Florida requires that grants of hot powers be initialed, but Virginia does not. The provision could work in Virginia without the requirement of initials.

Also interesting is the significance the court gives to the “do all acts” clause in interpreting other grants of authority. The inclusion of a “do all acts” clause is typically intended to support the broad construction of other grants of authority, particularly to support the interpretation of an arguably general grant as the grant of a hot power. We might address this in drafting by omitting the clause from powers of attorney. This is common in Florida, as Florida law does not give effect to “do all acts” clauses. Some of the lawyers in my firm take this approach.

Finally, this case raises questions about the adequacy of the default duties of agents under powers of attorney. Many of the Virginia lawyers who have commented about his case (to me or publicly) have mentioned the duty of an agent to preserve the principal’s estate plan. That duty can be waived in the power of attorney. To the extent the duty of an agent to preserve the principal’s estate plan applies, it might not prevent outcomes like the one in this case. There is more than one way to look at what constitutes someone’s “estate plan.” Frank’s “estate plan” could be the documents he signed, or it could be his documents and Jane’s. To the extent we want to bar an agent from altering any particular provisions of a document, we may need to connect those provisions to the duty in the power of attorney. We might, for example, prevent the agent from substantially altering the relative proportions in which the beneficiaries of the principal’s revocable trust (or will) receive the principal’s assets after the principal’s death—if that is what the principal wants.

As a thinking exercise (h/t Tom Yates), consider a variation on the facts of this case. Imagine an unscrupulous agent who uses the power of attorney to make him or herself the sole beneficiary of the principal’s assets, to the exclusion of all the other beneficiaries of the principal’s estate plan. Perhaps that would constitute a breach of the duty to preserve the principal’s estate plan—assuming the duty is not waived in the document. And perhaps such an act would be the “willful misconduct” for which the agent (under a power of attorney like Frank's) is not exculpated.[4] Assuming the outcome under these alternate facts should be different, how confident are we that it would be?

Footnotes

- I have included facts that were not in the opinion. I obtained the additional facts primarily from the briefs.

- She also used the POA to amend the existing trust, but that doesn’t bear on the outcome.

- The third provision begins almost like a further assurances clause, which we might not ordinarily read to grant a power to create a trust; however, the language specifying whom the trust may benefit seems to me to make the provision a grant of the power to create a trust.

- The exculpatory provision would be subject to the limitations of Va Code §64.2-1613, though it might not exceed them.